How we start projects: Spine and Constraints

We have spent 3+ years developing our first board game Beast Master. Part of the reason it has taken so long is that we fumbled around in the dark for the first couple years designing without any constraints or any particular goal in mind. A cool, divergent idea would come up and we had no grounds to say, “no, that’s too far fetched,” or, “that’s simply not what we’re aiming for here.” We ended up accidentally re-designing it into a completely different game more than once. We eventually landed on a game that both of us are proud of, but we spent lots of unnecessary time banging our heads against the wall.

Since then, we’ve started explicitly writing up two things that shape the development of our games: Spine and Constraints. These crucially important concepts provide a huge amount of clarity and focus for us, and give shape to our projects before we even start prototyping them.

Spine

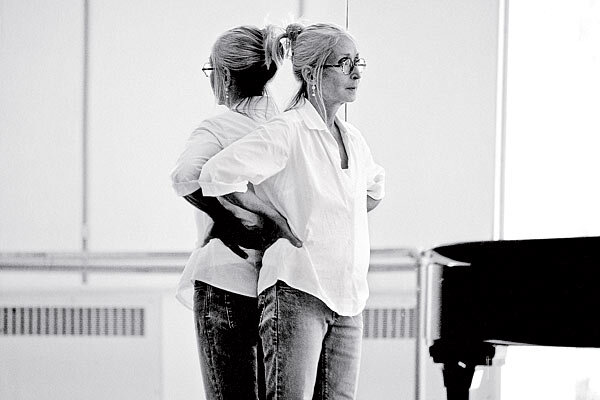

Twyla Tharp is a choreographer who has been creating and directing wildly successful dance productions for decades. I know little to nothing about the art of dance, but I know that she wrote a brilliant little book called The Creative Habit. It is chock full of practical ideas for how to lead a creative life and how to do creative work.

One of her stickiest ideas is that a great creative work needs to have a spine that holds it up. She describes a Spine as “private guidance” that can drive the theme and structure of the entire work. “The spine is the statement you make to yourself outlining your intentions for the work... The audience may infer it or not, but if you stick to your spine the piece will work.” The spine is pre-eminent, and it informs every single creative decision you make. You can create something without a Spine, but it will very likely lack coherence, conviction, and confidence.

Constraints

At GDC in 2019 Matthew Davis detailed how he and his team designed the game Into the Breach. I aspire to one day make something as deeply elegant, fresh, thoroughly explored as Into the Breach.

Their development was driven by the constraints that they put on themselves. Davis describes a “hierarchy of constraints” that they implemented as they developed the game. Their design process is a process of narrowing their own options. They’d lock one constraining idea into place (such as: players have perfect information about what the enemies will do next), then survey what was still possible in the game, and implement further constraints from there. They continued narrowing down the mechanisms in the game until the game was an immaculate, clear, and perfect piece of game design. This is similar to the concept we love of “soft vs. steel.” Once we find something that feels great, we throw out other soft ideas that fail to serve the ideas that are working. Once you have a few steely things working together, it becomes obvious what you need to cut, and the game almost begins to design itself.

Certainly there is a time for broad and unconstrained brainstorming. When I’m deciding what kind of project to take on next, it is worthwhile to be extremely open-minded and uncritically explore new and wildly divergent ideas. But once I’ve decided on a project that has a spine, it’s crucial that I set up some basic guardrails for myself to focus my creative thinking onto how to make the most of the confined little idea that I’m trying to develop. Without guardrails to guide brainstorms, the space of possibilities is simply too large to be manageable. This kind of focus makes mere concepts blossom into fully realized games.

Here’s a glance at what this looks like with the two most recent games we’re working on.

Rampage

Spine: you must build hands and manage your deck to win battles in a way that also prepares you for all contingencies, and preserves your best cards for future battles.

Constraints: less than 5 minutes to learn, both players have identical decks, the entire game consists of 54-108 cards, and game play must have enough variance to be extremely re-playable without adding more cards.

With Spine and Constraints in place, I was able to rapidly generate dozens of ideas for cards. Some worked and some didn’t. Some were interesting, but felt misaligned from the Spine I wanted. I was suddenly free to confidently shelve cool ideas and say, “no” because I had guardrails. I was able to really deeply explore this little idea of building multiple contingent hands, and the result is a focused and fun game that represents the best game design I’ve ever done.

Pecking Order

The Spine and Constraints of Pecking Order were borne of necessity. When Covid-19 hit, we were suddenly not able to test games in person, but we wanted to make a cut-throat social game that we could play together remotely.

Spine: All game play, sharing of asymmetric information, deduction, cooperation, and betrayal is handled through text communication, and players can communicate as much or as little as they want.

Constraints: less than 3 minutes to learn the rules, includes no components other than Discord or Slack, players don’t get eliminated, and game play should vary majorly depending on who is playing and how experienced the players are.

Designing a game with no components and few rules was extremely restricting. It forced us to think very differently about design and throw out loads of cool ideas that are simply too complex for this medium. What we were left with was a hyper-focused, and truly addictive game we can’t stop playing.